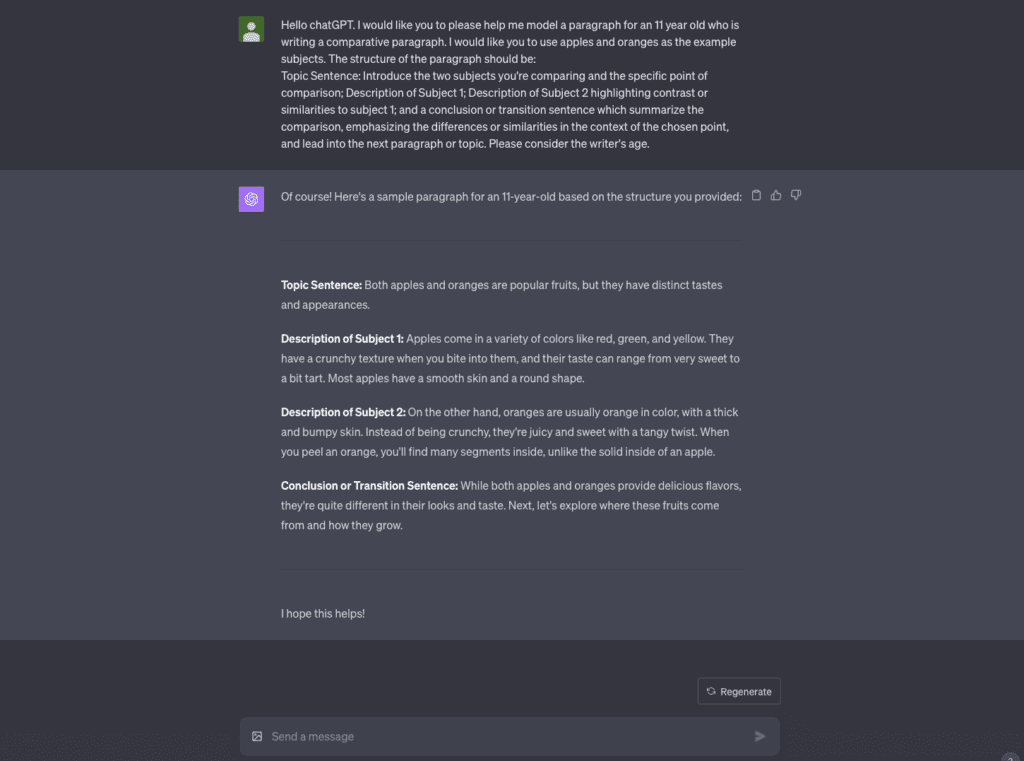

How to Quick Write at Home With Your Writer

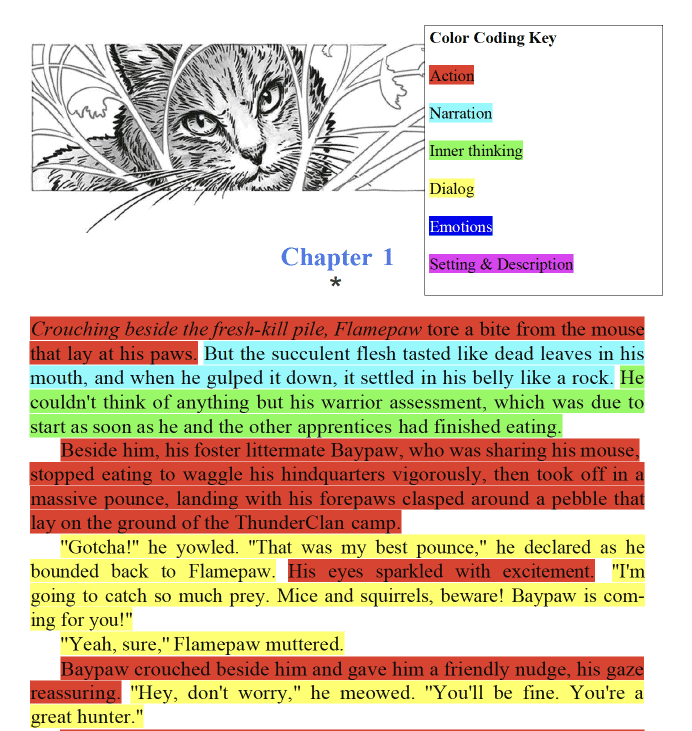

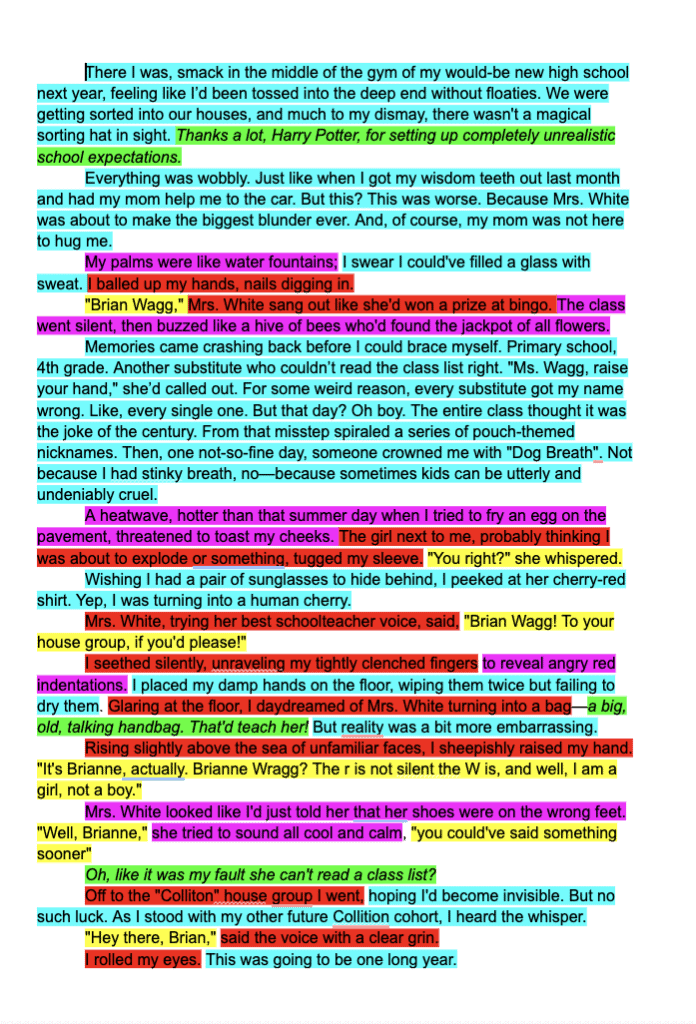

Imagine a space where your child can unleash their thoughts without barriers, where the clock encourages a thrilling chase of words. A Quick Write is this spirited sprint—a short, timed writing bout that challenges young minds to flow with creativity without the brakes of perfectionism.